Last week saw the de-pegging of yet another stablecoin.

Terraform Labs’ stablecoin TerraUSD (UST) depegged from the USD and hit $0.29 at one point. A further decline in the days following the initial depeg saw UST trading as low as $0.03 at one point.

With a market cap of approximately $18 billion before its depeg, such an event drew the attention of regulators who have been eyeing stablecoin regulation for a while. US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made sure to bring it up during her testimony before a US Senate panel hearing on financial risk.

Regulators have long set their sights on stablecoins. As blockchain-based technologies prospered in 2019, Group 7 (G7) nations that included central bank officials, ministers, and officials of the International Monetary Fund (among others) have raised an alarm over stablecoin regulations.

Among these investigations, they assigned a new term for stablecoins as Global stablecoins (GSC). The G7 mentioned that digital payments using cryptocurrencies are becoming more popular and have the potential to make payments easier, faster, and cheaper, but they can still pose a danger if risks are not addressed.

One major concern that the G7 has regards private authority control over the monetary supply of these stablecoins — such as Tether (USDT). The published report states several concerns such as the privatized authority of the global level monetary system, risks of disruption of financial stability, transparency of reserves that are backed to peg the coin, and cross-border transactions among other concerns.

Following this, G20 nations also put forward 10 high-level recommendations by the Financial Stability Board in order to promote consistent and effective regulatory, supervisory, and GSC oversight.

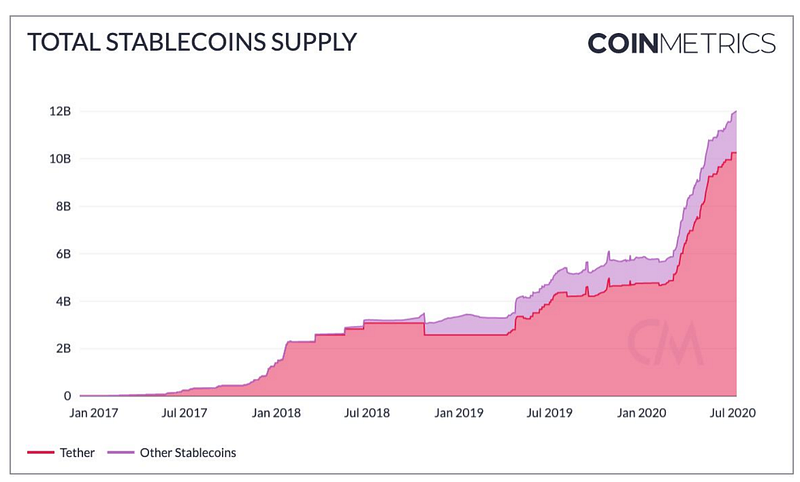

While the regulatory side of GSCs gain increasingly more attention from officials, market growth has significantly grown since 2019. USDT first introduced stablecoins to the crypto world in 2014 with a simple concept to back each USDT to USD with fiat reserves held in various forms.

After launching on the Tron blockchain in 2019, USDT’s market cap boosted its expansion throughout the crypto space and heavily dominated the GSCs. From 2018 to 2020, many other fiat-backed stablecoins were introduced such as USD Coin (USDC) by Circle, Binance USD (BUSD) by Binance, Gemini USD (GUSD), PAX by Paxos, True USD (TUSD), and Terra USD (UST) by Terraform Labs, just to name a few.

Currently, the global stablecoins market cap is ~$181 billion, which is almost three times higher than one year ago. Although the market cap is only ~10% of the global crypto market, the rapid growth of GSCs concerns financial regulatory boards and officials regarding preventing the disruption of traditional financial systems and minimizing risks, as well as fraudulent activities that can lead to market failures.

There are several concerns raised in the G7 nations’ reports related to the GSCs, but in this article, we will address four main issues which are specific to the top six stablecoins: USDT, USDC, TUSD, DAI, UST, DAI.

Reserves and liquidity

Stablecoins are highly important in the crypto world. As most people tend to refer to asset prices in relation to fiat currencies such as USD, pairing crypto assets to stablecoins has brought freedom to the crypto markets and a degree of stability.

When Tether introduced USDT, it became the most used medium of exchange mainly on Ethereum and Tron blockchains. USDT had almost 100% market dominance until the introduction of new stablecoins in the following years; it fell from ~75% in 2019 to ~45% at the time of this article. The following table shows the present market supply for six different stablecoins*:

Currently, most GSCs are highly privatized. A few are decentralized such as UST and DAI which are governed by communities and do not have one central authority. However, fiat-backed GSCs are extremely liquid because corresponding issuers maintain the peg by partnered exchanges.

The concern of stablecoin to USD liquidity is a risk because exchanges and the coin issuer can pose limits on redemptions if they run out of USD liquidity. Additionally, most crypto investors don’t use stablecoins as a store of value because they are pegged to fiat currencies. Hence, similar to USD, a USD-backed stablecoin is also an inflationary coin that cannot generate yield by itself. In order to generate yield, the stablecoin has to be exchanged for a crypto asset either on an exchange or a money market.

Transparency

Blockchains and cryptocurrencies are reputed to have the most transparent and immutable databases. However, transparency is questioned when it comes to reserves that are backing their stablecoins. If GSCs are only used within the crypto ecosystem, issuers can show reserves equal to coin supply. However, if stablecoins are linked to fiat currencies, which is common, total reserves need to be equal to or more than the total market supply (overcollateralized). And to keep the issuers’ reserves constantly in check, regulators need to interfere and enforce them to conduct valid audits every time period.

Following these regulatory recommendations issued by G20 nations after the G7 report, all issuers are declaring audits from 2019. Followed by such interference by officials, Tether Ltd. released an affidavit in 2019 stating that USDT was only 74% backed by cash reserves, which led to lawsuits and settlements. Concerns also grew with the growing USDT market supply. To address this, Tether redesigned its official website to enable a “Transparency” section where reserves are updated daily.

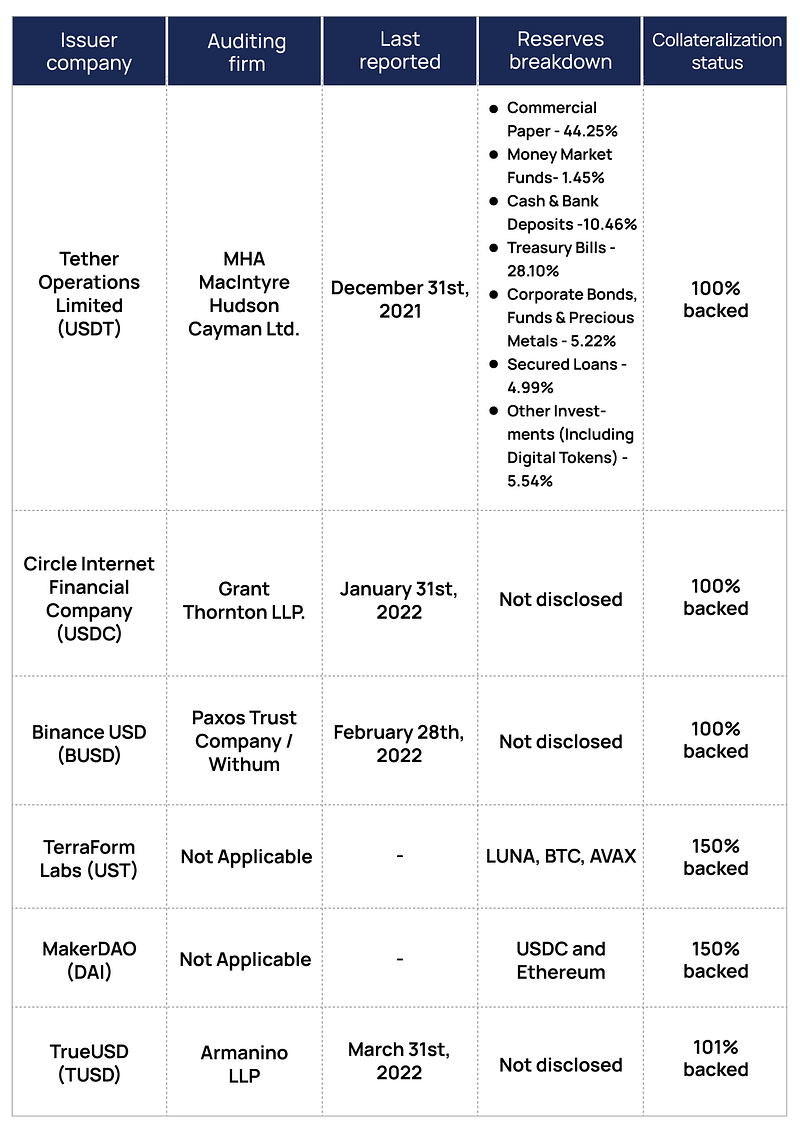

The USDT’s transparency was last audited and reported on December 31, 2021, by MHA MacIntyre Hudson Cayman Ltd. The audit found that Tether holds the majority of its reserves in the form of commercial papers rated A-1 and A-2. A deep-dive analysis on USDT’s opportunities & risks was conducted earlier along with reserves and auditing reports breakdown.

Contemporarily, transparency is a subject to declare reserves for stablecoins by issuers and auditors to examine and validate claims. However, most GSCs have only disclosed a consolidated form of reserves being held — but no information available on investment breakdown.

However, Circle Internet Financial Limited reported its reserves are 100% collateralized for the USDC supply, but the reserves breakdown isn’t released to the public. In response to Rep. Nydia Velázquez’s question at a hearing, CEO of Circle Jeremy Allaire stated, “Yes, I can confirm that 100% of the reserves that back USDC are held in cash and short-duration US Treasuries” (source). Similarly, BUSD and TUSD also released attestations declaring that their reserves are equal to or more than 100% backed.

No doubt that government regulation intervention over stablecoin reserves had improved transparency better now than ever before. Consequently, this puts the issuers under pressure to deposit reserves in banks that aren’t generating much interest rates for the issuer’s profits.

Regulatory perspective

Since most jurisdictions do not have regulatory standards for most cryptocurrencies and GSCs, they operate based on the “same business, same risks, same rules” principle (source), where a relevant existing regulation is applied to that activity or entity which the stablecoins perform.

A stablecoin could fall under more than one regulatory category and as a result, its classification can change as its nature and use evolves. For example, fiat-backed stablecoins used for digital payments can be considered e-money which can be regulated by the FinCEN in the US or by the Payment Services Act — 2019 in Singapore. In a 2020 report, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) stated that there are merely 33 jurisdictions available that can be applied to issue/redeem stablecoins; there is also more than one jurisdiction available over many regulations that include: FMI/payments, investor protection, market integrity, data privacy, and cyber security among others.

GSC regulatory concerns also include licenses to conduct operations. The basic operation of any stablecoin is to transfer money which requires issuers to acquire a transmitter license. Fiat-backed stablecoins such as USDT, USDC, BUSD, and TUSD are acquiring transmitter licenses along with local state licenses in order to issue coins. However, algorithmic stablecoins that don’t have a responsible central entity are out of regulatory aspects, which can be a concerning risk toward anonymity as well as the risk of disrupting the financial ecosystem if the liquidity concentration increases. Those risks can be mitigated by enforcing KYC mandates and allowing access to AML compliances similar to fiat-backed stablecoins.

Fiat-backed stablecoin issuers Circle, Paxos, and TrueCoin have registered with regulating bodies and can provide issuing and redeeming services in the US, but less so outside of the US. Tether, on the other hand, is restricted access by US residents but has been widely used in many other parts of the world outside the list of restricted nations. Paxos is on a shopping spree for those licenses and has recently acquired an MAS-issued license in Singapore, which has been a tough one to crack by more than 100 crypto-based companies.

Operational risks

Depending upon the type of stablecoins, operational risks vary. Fiat-backed stablecoins such as USDC, USDT, BUSD, and TUSD which are either run on a centralized or partially decentralized ledger, pose the risks of asset custodianship, wallet suspension, poor treasury management, and cyberattacks on the central entity. Whereas the algorithmic stablecoins that are run by digital autonomous organizations (DAOs) on a distributed ledger can carry risks of having poor governance, less control during de-pegging events, and little prevention of fraudulent transactions.

Fiat-backed and algorithmic stablecoins come with their own risks and benefits. The central entity holds the responsibility to ensure the reliability of custodians and trustees, ensuring the capacity of the network is capable of processing large volumes of transactions without network congestion, and of an efficient validating system.

For algorithmic stablecoins, DAOs need to operate through the governance system to make improvements to networks and infrastructure and act against cyberattacks, which can be slower in nature compared to a centralized approach. Data shared on public ledgers is an open book with immutability, auditable, and traceable at any time. However, to those who need an extra layer of security to enable privacy, centralized entities can provide standard solutions in compliance with AML-CFT requirements, which is unlikely in the case of decentralized stablecoins due to the lack of oversight.

In case of de-pegging events for fiat-backed stablecoins, companies can source deposits and establish the peg with little repercussions. In a macro view, when the stablecoin supply surpasses the threshold of 50% of the fiat supply, pressure builds and may lead to financial ecosystem disruption.

In the case of algorithmic stablecoins, especially for DAI and UST that require minting/burning of MKR and LUNA respectively, the peg may never stay constant but incentivizes the arbitrageurs to maintain the peg while varying the demand-supply for tied assets. In spite of that, de-pegging can be a risk if the demand for the coin falls below the threshold.

A perfect example here can be the fall of Iron.finance where IRON lost its USD peg and the value of its corresponding coin TITAN fell to zero due to inadequate price feeds by oracles, which cost $2 billion in total value locked for the protocol. The event of such peg destabilization can happen in several ways; being a democratic system where people are decision-makers as well as investors, the panic can lead to chaotic downward selling pressures before even being able to act upon the issue.

Conclusion

This article shows the downsides and upsides of top stablecoins and briefly explained them by addressing major concerns about their reserves, transparency, and regulatory and operational risks. The effects and ramifications of some risks are hard to quantify given the absence of a single GSC that is operable globally under all jurisdictions.

The GSCs’ growth (and demise) has put regulators under serious pressure to confront the innovation that is offering more opportunities, security, speed for faster settlements, and an adaptable economical niche for rapidly changing customer needs and demands.

Authorities need to work on recommendations and solutions for fundamental issues across diverse economies and legal systems with international coordination, instead of only pointing out GSC risks and dangers. The collapse of UST showed that GSC-specific regulation is much needed to audit fast-growing GSC firms such as Tether, Circle, Paxos, Binance, Trucoin, and Tron to ensure illicit strategies are prevented and all risks are mitigated.